SUMMER DRAW - MAPS & MYTHS

Maps and Myths, what is not to like? Two subjects that fascinate children and adults alike, with both providing a way to decipher and make sense of the world around us.

Maps are beautiful objects in and of themselves. They help us find a way through difficult terrain and are a perfect metaphor for navigating life’s tricky journeys. And so it is with mythology, a term that combines two Greek words: mythos roughly translating to ‘story’ and logos referring to ‘spoken word’.

As spoken stories, myths provide a way of speaking about the divine, and of forces and powers bigger than the human. They create meaning and framework for many different cultures and are often incorporated into organised religion, ritual and folklore.

Today, public reference to the divine no longer sits so comfortably with the evidence-based language of science and technology, instead such talk is seen as belonging to the realm of the private and personal.

Yet, these stories haven’t entirely left the public eye, rather they have been honed, recast and presented into new and different forms and media. The Norse God Odin and the almighty Greek Zeus may no longer wield any power, but we still crave after stories that speak of forces greater than our own. Whether following the super heroes of Marvel Comics fighting against corporate greed, or binge watching the televised series of children with superpowers battling monsters from an underworld created by a scientific experiment gone horribly wrong.

Art, theatre, film, fiction and popular culture provide a place where we can express our emotions and confront our innermost fears and terrors, a notion espoused by Aristotle, the Greek philosopher nearly 2500 years ago. These are the spaces where public and private meet; where concrete materiality and the current laws of known physics can be suspended, at least for a short time, allowing us to collectively sink into stories that fire the imagination.

MAPS

Maps can be seen as abstractions of the space around, and, within us. Whether maps of the body or maps of the night sky, each are projections and interpretations of space, simplified down to often just a series of dotted and dashed lines that ring-fence, contain and make sense of space.

Star maps are perhaps the most abstract of all, presenting a system of lines that combine myth and story whilst helping us as mere mortals to make sense of where we are in time and space. The shapes of Pegasus or Orion the Hunter are only projections onto stars that are light years apart from each other. Yet, viewed from our earthly station, these fictional dot-to-dot lines help us to find our way across oceans and through life.

STRANGE ANIMAL

The many stories of mythical animals, from the magnificent Griffen, combining the strength of a lion and the powerful flight of an eagle, to the Phoenix and its wondrous ability to resurrect and regenerate over and over, represents our fascination and affinity with the more than human world.

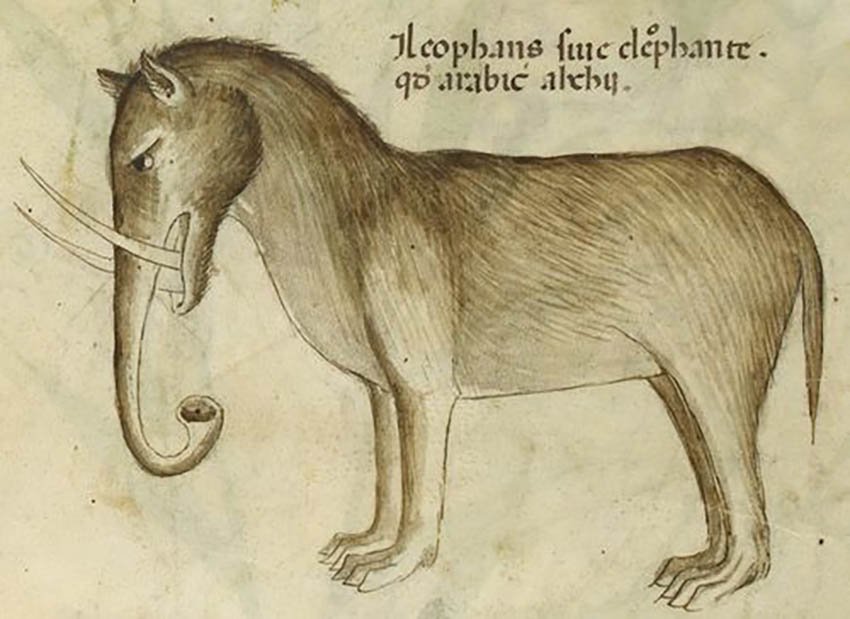

Often in the past, artists were unable to directly observe their animal subjects and instead had to make drawings from second-hand stories—a process that resulted in many strange depictions as seen in the examples below.

Look to the night skies to see how many constellations are named after animals. In the so-called “modern” or western skies, there are 42 animal constellations, including Ursa Major (the Great Bear), the Bull, and the horse bodied human Centaur, compared to 14 constellations named after humans. Animals equally dominate the “sky cultures” of the Chinese, Maori, Navajo and Tupi, as well as the historical cultures of the Aztecs and ancient Egyptians.

Stories of humans shape-shifting into animal forms abound in every culture. The story of the ‘Selkie’ is a Celtic and Norse maritime legend that speaks of a sea people able to move from the body of a seal to human and back again by donning a cloak of seal skin. Interestingly, ancient drawings of Selkies look remarkably like a foetus, or an early embryonic form that could be either human, dolphin or seal, a reminder of our shared evolutionary and aquatic links and perhaps the origin for such stories?

SUMMER DRAWING ACTIVITIES (for young artists, or adults if they are so inspired)

Drawing 1. Create your own mythological creature, combining two, or possibly more different types of animals. Like the Griffen, a merging of an eagle and lion, think about what features you will draw in your new animal.. Where does this new being live, what is it called and how does it behave?

Suggestions: select one colour alongside black or dark grey, like in Siyu Chen’s drawings. Perhaps this new animal may inspire you to write a story!

Drawing 2. Draw a map of where you live. Will you draw it from above, with the roof off, or perhaps from the front looking in, similar to a dolls house.

Consider what you will include in your map. Will you include the tree by the front door, the television, or the spider that lives in the corner of the bathroom?

Drawing 3. Create a map of your own imaginary world. Will it be in the future or past, on the moon, underground or beneath the ocean? Perhaps it exists in a dream space or a parallel universe — the choice is entirely yours. Draw the animals that live in this new world, perhaps there are dragons and hob-goblins or an entirely new species?

Image references

Japanese Match Box Map, date unknown, c. 1920s

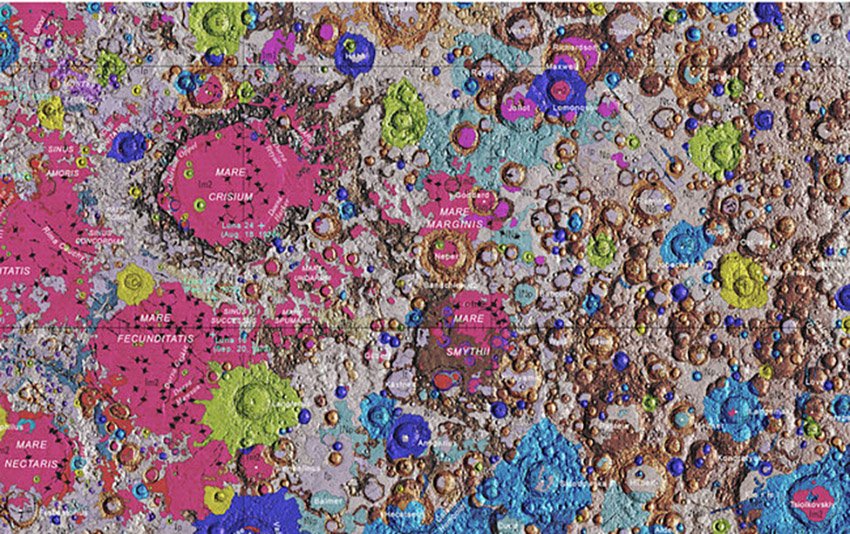

NASA Moon Map, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the Lunar Planetary Institute.

Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-43, MOMA. Oil on canvas, 127 x 127 cm.

A Dragon Flying over a Panther, (detail) in a bestiary, about 1270, possibly made in Thérouanne, France. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 3, fol. 88. Courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Detail of a miniature of an elephant; from a herbal, Italy (Lombardy), c. 1440.

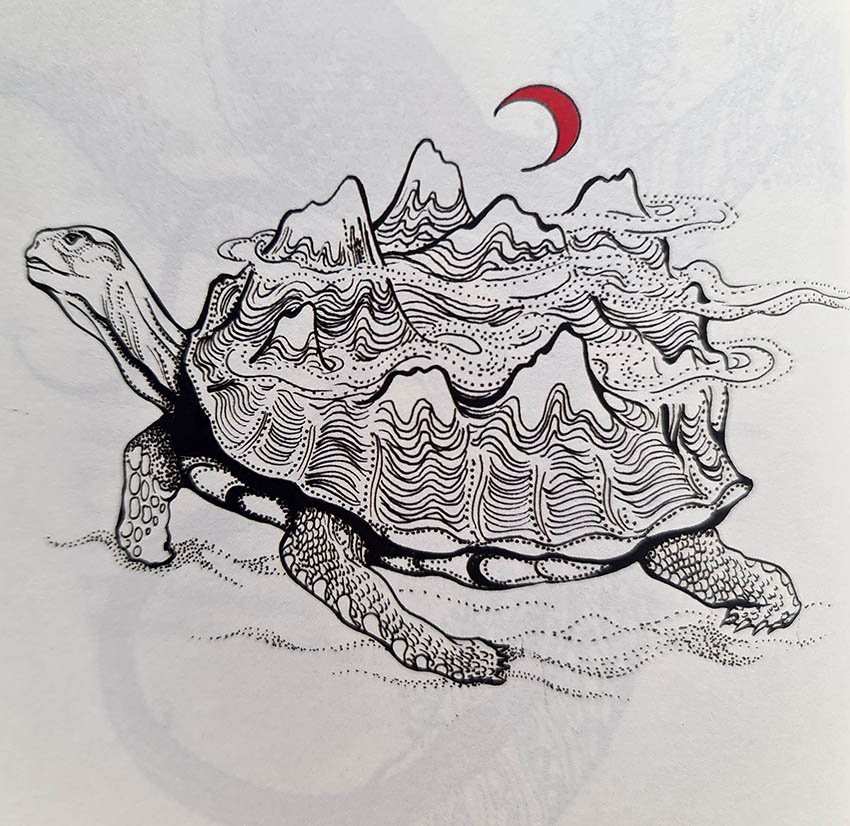

Illustration by Siyu Chen, featured in the exquisite Fantastic Creatures of the Mountains and Seas, 2021, Arcade Publishing, New York. A book that explores Chinese mythology with beautiful illustrations by Siyu Chen. Here the three-legged turtle known as Sanzugui from the Kuang River is able to protect people from horrible illnesses.