You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.

Maya Angelou

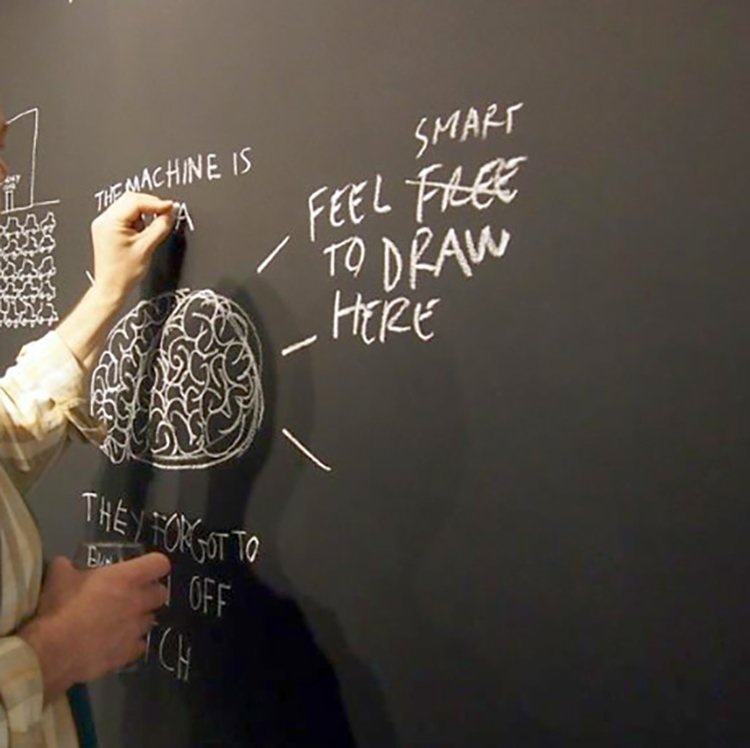

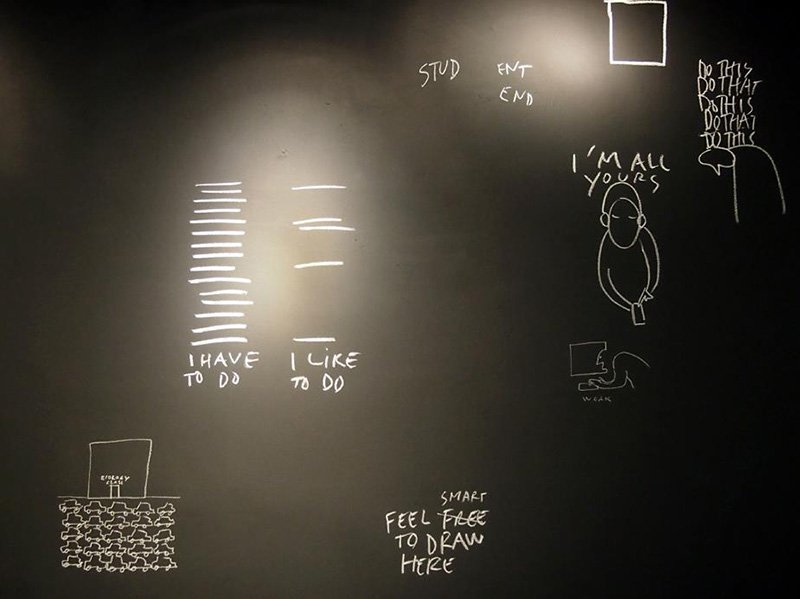

DRAWING AS A PRACTICE

Drawing is a way of noticing. As artists we can train our eye to see the shape of things, looking beyond the clichéd view to find delight in the hitherto unnoticed and unappreciated.

Stop, look and see. Scan the room and observe the order, chaos, dirt and beauty. Look outwards and then inwards. Notice the wilting plant, the edge of the leaves frayed by the power of the August sun. Watch the cast of light heightening texture and colour and savour the sap green and burnt umber, the colour of caramelised sugar.

In the Shaivite tradition, some names for God can be translated as “attention,” “consciousness” and “awareness.” Such naming suggests that attention itself might be perceived as God. In a similar manner, the word “enthusiasm” comes from the Greek enthusiasmos, with en meaning “in” or “within”, and theos referring to the Divine.

Similarly, science has found a parallel, not quite with godliness, but at least between the act of awareness and obtaining a state of happiness, with recent studies showing how people describe themselves as being happy when they are paying attention, and unhappy when they are not.*

In a world of distractions and constant scrolling and flicking of channels it perhaps comes as no surprise that poor mental health outcomes are the highest they have ever been, particularly amongst the young.

By comparison the act of drawing demands a period of attention and focus, be that internal or external, of being with the observed subject.

You can lose yourself in drawing, and in this way drawing can be seen as a mindful activity, fitting quite naturally alongside mediative and yogic practices.

Yet, it is important to acknowledge the sometimes fraught tussle between observation and interpretation. What we see, or, imagine what we see, is invariably not what appears on the paper. This gap can often be frustrating. But, it is precisely in this space, between expectance and outcome, where the essence of creativity lies. Your unique voice and way of seeing will be captured in the line.

To draw is to learn, and as such drawing is as much about learning to recognise and appreciate your own articulation of the world, as it is about observing the subject at hand.

The more you draw, the more you will see.

Sketchbook exercise - some tips.

1. Draw regularly. Get a sketchbook and treat it as you would exercise - five, ten, 20 minutes to observe and draw. Remember, like physical exercise, it takes practice to see an improvement, and regular drawing will help develop new muscles and ways of seeing.

2. Undertake a series of quick sketches: a plant, coffee mug, your hands—keep the subject simple. Give yourself a time limit of two minutes for each drawing. Do several quick sketches and do not worry whether the drawing looks right or wrong. This is a warm-up exercise and it helps you to make quick decisions about proportions and composition without over thinking. It also gets you used to moving on quickly to new drawings without getting overly precious about one image.

3. Look at the work of other artists — lots and lots.

* M. A. Killingsworth and D. T. Gilbert, “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind,” Science 330, no. 6006 (2010):932.